Today we continue our Mewsing on scratch-building USS Cumberland in a bottle. (You can find Part 1 here.)

With Cumberland rigged and painted, it was time for Rebecca to put it in the bottle. First, she dabbed blobs of Duco Cement inside where Cumberland would rest. Then she had to get the ship in place before the glue dried. How much time did she have? She had no idea. Meanwhile, Ruth had the presence of mind to take a video of the ship going into the bottle. It took six minutes to finagle the hull and masts in, but Cumberland made it, with all rigging, sails, and spars intact. And the glue hadn’t dried yet, so the hull nestled into place just fine.

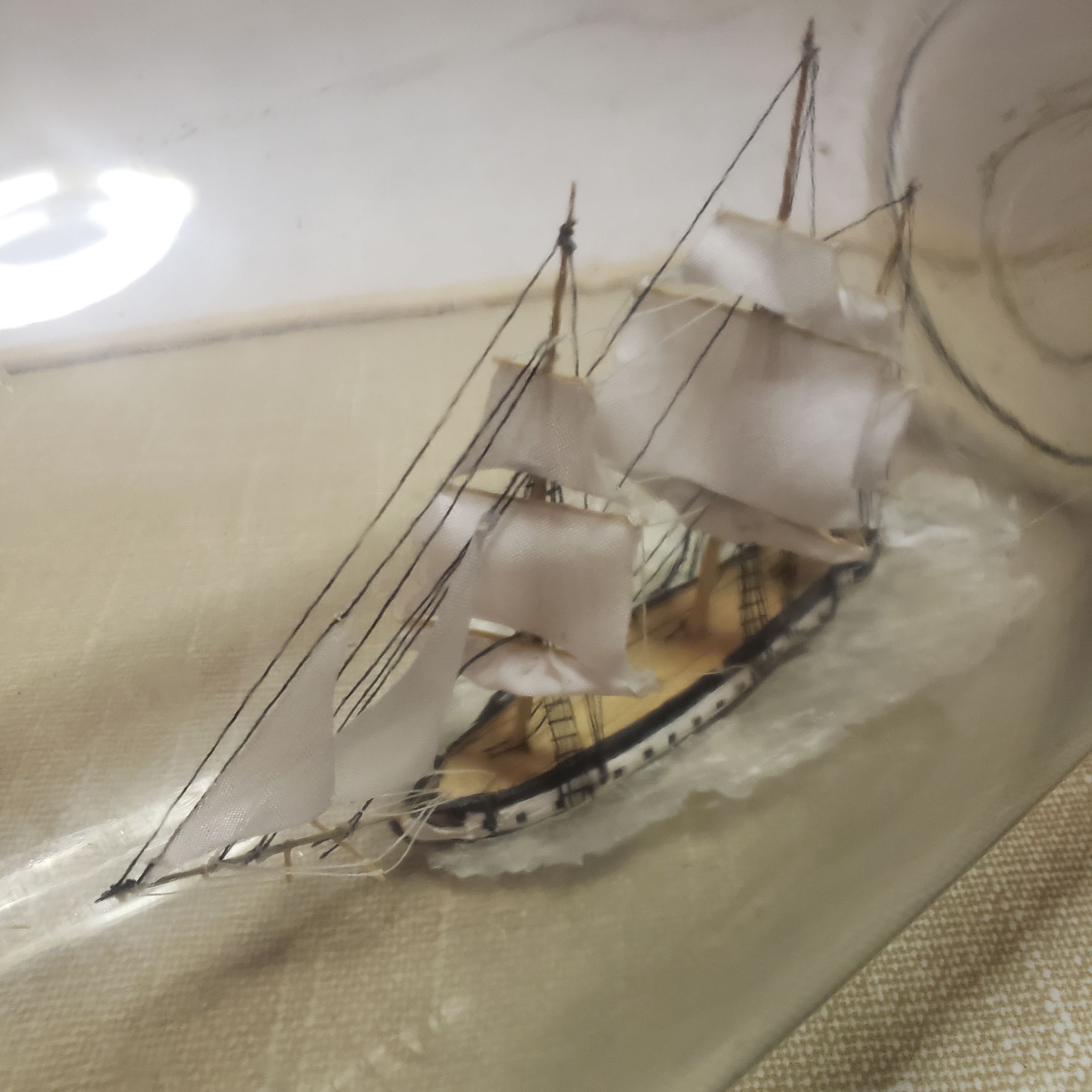

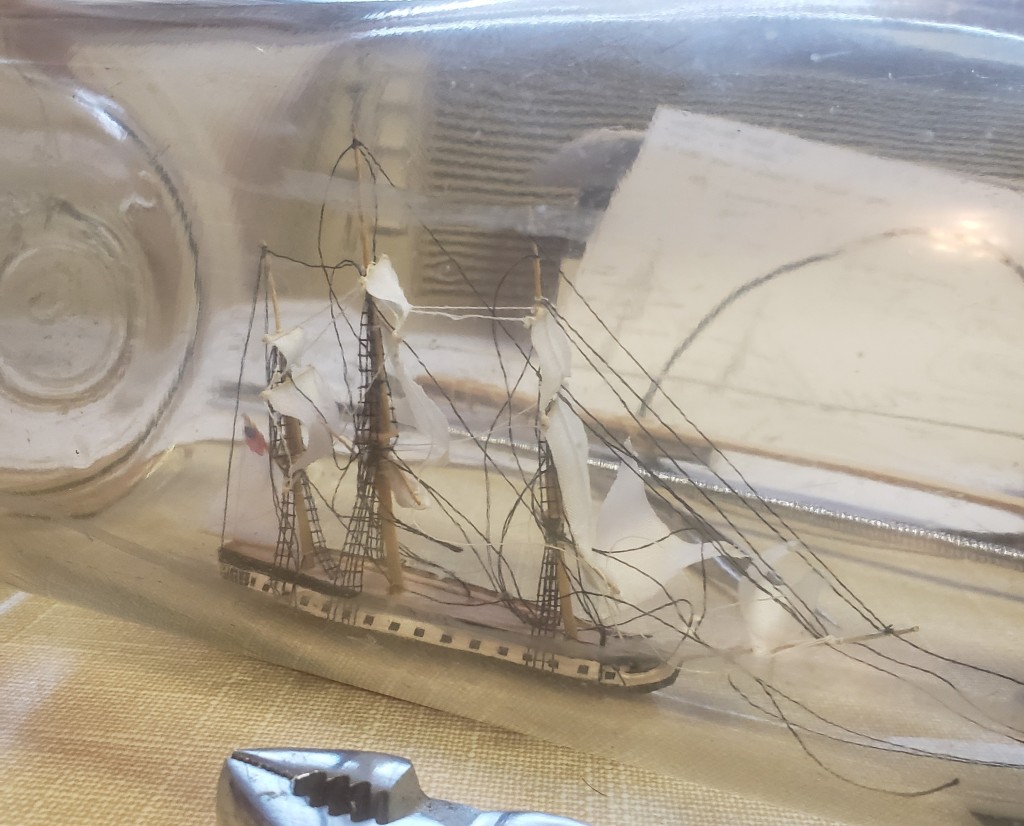

Once Cumberland was securely fixed down, Rebecca inserted the sides of the hull and raised the masts. Then followed several evenings of gluing rigging into place. With a kit, the shrouds and stays are attached to the sides of the ship before it goes into the bottle. Here, Rebecca had approximately 30 strings to glue, after the insertion. And she could only do three at a time before going bonkers! After finishing the ship, she added waves made from Liquitex Gloss Super Heavy Gel, the medium we use for the water effects on our dioramas. On May 16, 2022, Cumberland was done!

The tools of the trade:

In the foreground is our “grabber-thingy,” a contraption with a button on one end that you push to extend four claws out the other end. It’s awesome for navigating inside a bottle! Rebecca was even able to align the claws precisely enough that they could grab a single thread and pull it tight.

In the middle is a piece of model railroad rail. It has a cross-section like an I-beam, and that shape allowed it to hold down threads, pull them away, etc.

In front of the bottle is a piece of coat hanger. Rebecca twisted some wire around one end into a little hook, and it was helpful in manipulating rigging. The plain end could hold threads against the hull until the glue set.

Cutting the threads took some ingenuity. Xacto knife blades rubber-banded to a stick or the railroad rail worked pretty well.

A little about the bottle itself:

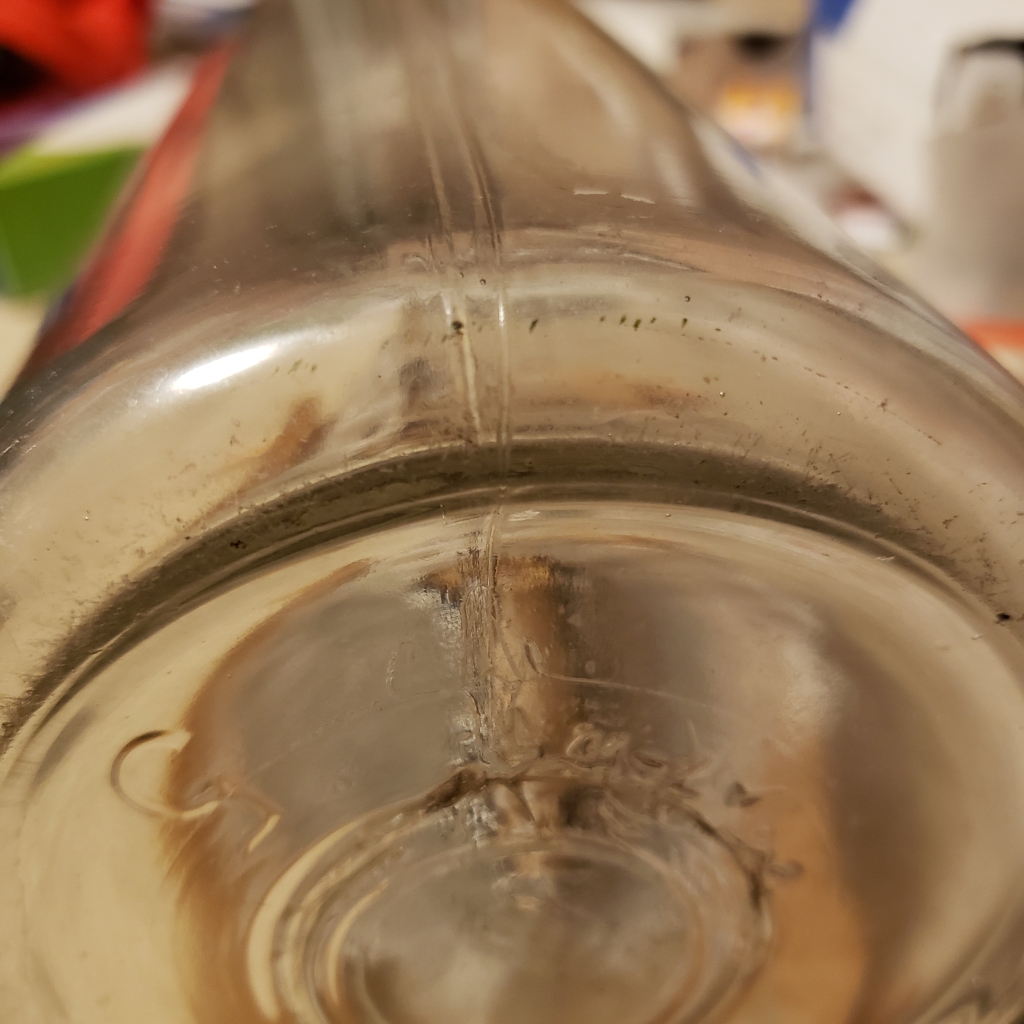

Judging from indications on the bottle, it dates from ~1905 to the early 1920s, but most likely 1911-1917. The suction scar on the base and the “ghost” seam on the side show it was made on a blow-and-blow Owens Automatic Bottle Machine, and the feathering on the suction scar indicates an early Owens machine. The single-letter code “O” on its base suggests it was made by the Owens experimental factory (Factory No. 1) in Toledo, Ohio, before June 1917, when they began using a different style of code. The “O” could also be to differentiate between the Owens Factory No. 1 and the Northwestern Bottle Company (code “N”) which was designated as Factory No. 2 in 1911.

The type of “lightning” stopper suggests it may have held a carbonated beverage (such as beer or soda). Our stopper, in particular, is a porcelain Hutter stopper. On the stopper is printed “E.M. Cook, Market St., Phila.” The only reference we could find online of E.M. Cook of Market St., Philadelphia, was a 1921 advertisement in the Philadelphia Inquirer which mentions them as a dealer for Imperial Cabinet whisky.

All I can say is wow. Lots of patiences and a steady hand. Lot it.

LikeLike

Brilliant…! Have to stop by and see it!!!

LikeLike