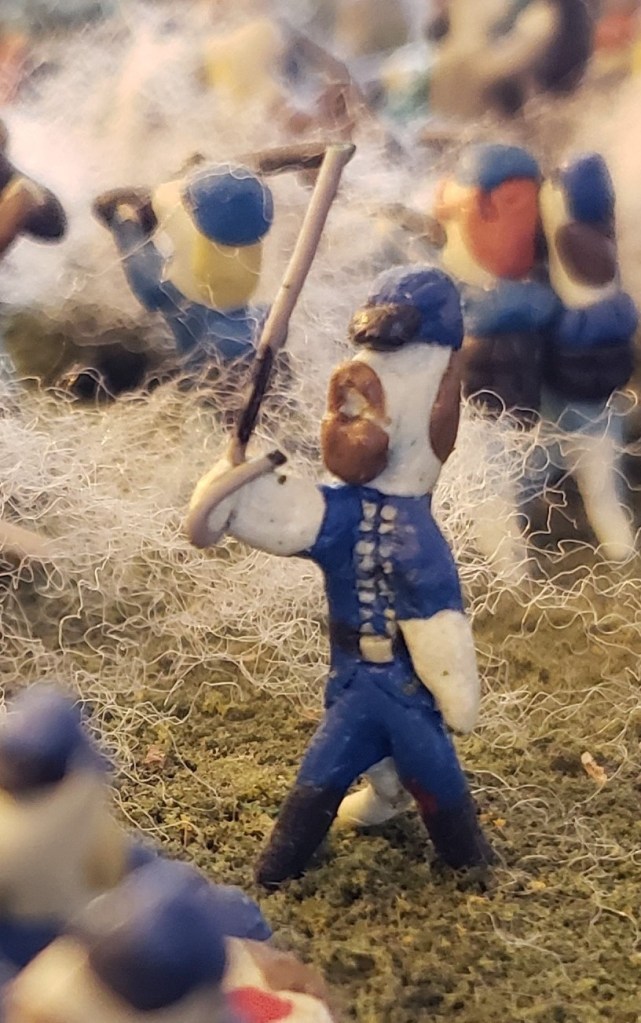

Yesterday was the anniversary of the battle of Antietam, in Maryland, on September 17, 1862. In today’s Mewsing, we take a look at the story of the final Union push across Burnside’s Bridge, which inspired one of our older “retired” dioramas.

Around 10:00 a.m., Gen. Ambrose Burnside received orders to attack across Antietam Creek. In response, one division attempted to cross at a ford downstream while a brigade crossed the bridge. Unfortunately, the ford was unusable, so those troops had to search for another. At the bridge, the 11th Connecticut, acting as skirmishers, attempted to cross the bridge and creek. Heavy fire cut down a third of the regiment in less than a quarter of an hour. Meanwhile, the brigade itself got lost and never reached the bridge. Another attempt was ordered, but that brigade faltered under fire from sharpshooters before reaching the bridge.

By now, Gen. George McClellan was getting antsy. He ordered Burnside to “push forward… without a moment’s delay.” In response, the frustrated and offended Burnside ordered Col. Edward Ferrero’s brigade to make the next attempt.

Ferrero formed two of his regiments, the 51st New York and the 51st Pennsylvania, into line. “It is General Burnside’s special request that the two 51sts take that bridge,” he told them. “Will you do it?”

At first no one said anything. Not only did the troops not particularly respect their brigade commander, but the Pennsylvanians were especially upset with Ferrero after he had denied them their daily shot of whiskey. Finally, Corporal Lewis Patterson called out, “Will you give us our whiskey, Colonel, if we take it?”

“Yes,” the colonel thundered in his “stentorian” voice, “You shall have as much as you want!”

Satisfied, the regiments advanced. The plan was to cross the bridge in two columns, four abreast, then the New Yorkers would turn to the left and the Pennsylvanians turn to the right, and they would form a battle line. But the Confederates poured a heavy fire on them as they advanced down the hill to the bridge. The columns broke up; the New Yorkers scurried to the left and hid behind a rail fence, and the Pennsylvanians scurried right and hid behind piles of rails and a stone wall. They fired across the creek at the Confederates from the slight protection of those positions.

The Pennsylvanians’ colonel, John Hartranft, yelled himself hoarse trying to urge his men on. Finally he rasped, “Come on boys, for I can’t halloo anymore.”

After about an hour, the Confederate fire slackened and Capt. William Allebaugh of the 51st Pennsylvania dashed onto the bridge, followed by the color-bearers, his first sergeant, and the color guard. The rest of the regiment swarmed after them, joined by the New Yorkers.

Across the creek, the Confederates were low on ammunition and aware that the Union division downstream had finally found a ford. Not wishing to be flanked, the Confederates withdrew.

A few days after the battle, Col. Ferrero was promoted to brigadier general. But he hadn’t held up his end of the bargain with the 51st Pennsylvania. So, as the regiments stood in their ranks at the promotion ceremony, Cpl. Patterson commented in a loud mutter, “How about that whiskey?” Ferrero got the hint, and the Pennsylvanians finally got their whiskey.

Reference: Bailey, Ronald H. The Civil War: The Bloodiest Day—The Battle of Antietam. Alexandria: Time-Life Books, 1984.

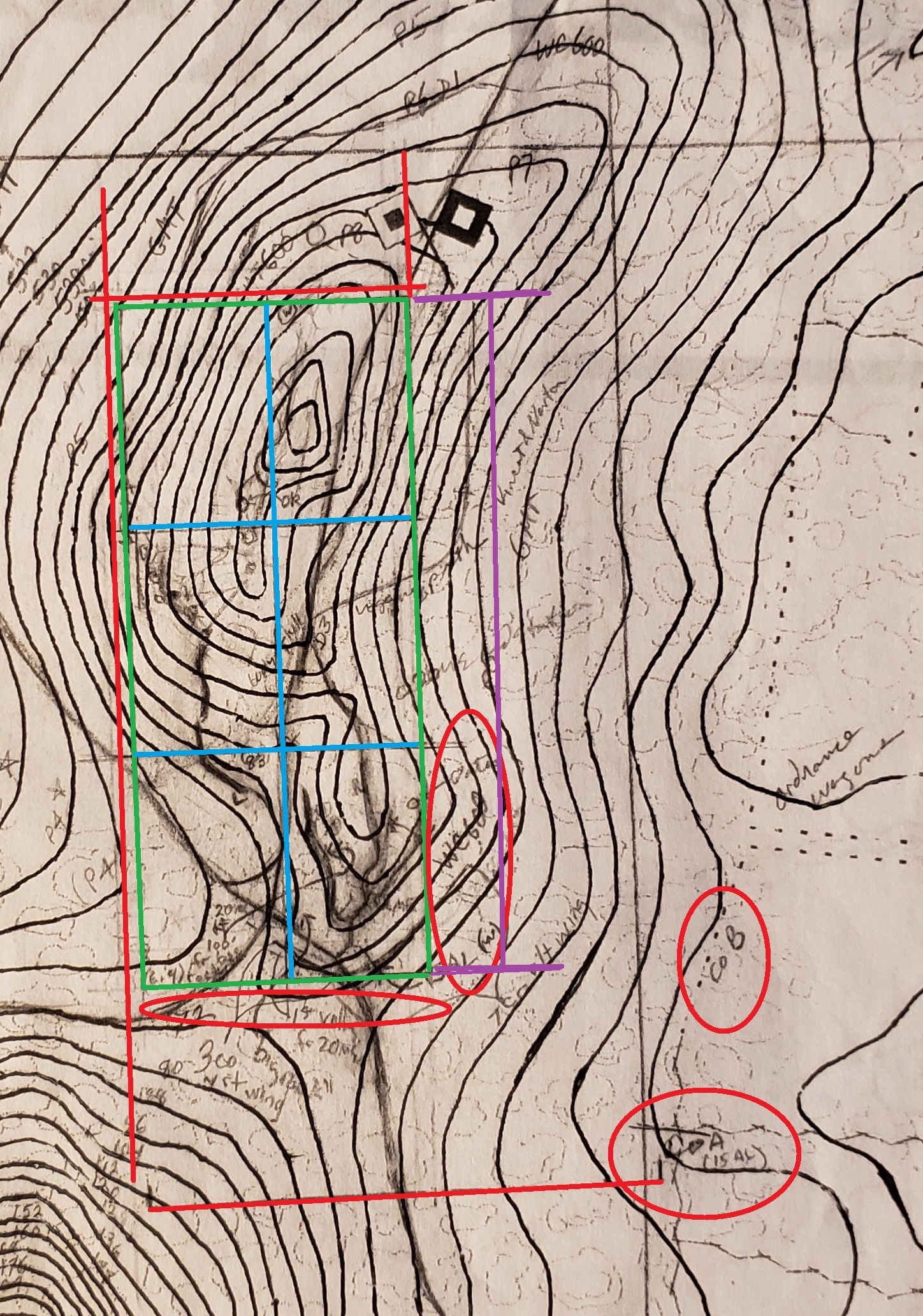

Before installing the limber on the diorama, Rebecca had to measure out the location. A photo from the early 20th Century shows a memorial gun tube near a particular boulder along the path to the castle-like New York monument, indicating the placement of one of Hazlett’s guns. The cannon in the background of this photo is located at that rock. Artillery pieces were typically placed 14 yards apart, so Rebecca measured the distance for a 1:96 scale (3/4” tall cat) from that cannon and boulder. Then, it was just a matter of placing the limber and gun #3 (the latter is not installed yet) where the rocks would allow for wheels and horses.

Before installing the limber on the diorama, Rebecca had to measure out the location. A photo from the early 20th Century shows a memorial gun tube near a particular boulder along the path to the castle-like New York monument, indicating the placement of one of Hazlett’s guns. The cannon in the background of this photo is located at that rock. Artillery pieces were typically placed 14 yards apart, so Rebecca measured the distance for a 1:96 scale (3/4” tall cat) from that cannon and boulder. Then, it was just a matter of placing the limber and gun #3 (the latter is not installed yet) where the rocks would allow for wheels and horses.

The hunt stems from one that Rebecca made the other day for a young visitor to the museum. We began talking about corps badges, which you can see on our Little Round Top diorama’s Union cats. But did you know they are on the monuments around the battlefield? Ever wonder why one monument has a star, another a crescent moon, another a diamond? Those are all corps badges, which were a source of great pride for each unit of the Union Army of the Potomac. See how many corps you can identify! You do not need to know about the battle to do it. But if you are a buff, you can still have fun with it! We also invite you to find each of the most common types of artillery on the battlefield. Think all cannons look alike? Think again!

The hunt stems from one that Rebecca made the other day for a young visitor to the museum. We began talking about corps badges, which you can see on our Little Round Top diorama’s Union cats. But did you know they are on the monuments around the battlefield? Ever wonder why one monument has a star, another a crescent moon, another a diamond? Those are all corps badges, which were a source of great pride for each unit of the Union Army of the Potomac. See how many corps you can identify! You do not need to know about the battle to do it. But if you are a buff, you can still have fun with it! We also invite you to find each of the most common types of artillery on the battlefield. Think all cannons look alike? Think again! Once you have completed the scavenger hunt, you will be able to go home and tell your friends or school teacher, “I learned the difference between a Napoleon smoothbore cannon and a Parrott rifled gun” or “Hey, that star makes me think of the XII Corps’ badge.” Maybe your friends won’t be impressed, but your teacher will be!

Once you have completed the scavenger hunt, you will be able to go home and tell your friends or school teacher, “I learned the difference between a Napoleon smoothbore cannon and a Parrott rifled gun” or “Hey, that star makes me think of the XII Corps’ badge.” Maybe your friends won’t be impressed, but your teacher will be!

The next consideration is scale. For a small scene, such as “Desperation at Skull Camp Bridge,” we could use a larger scale because the scene would not involve a lot of figures. A scale of 2-inch-tall cats is okay if there are only sixty soldiers involved. But it would be impossible to use cats of that size for a to-scale diorama with 3,000 soldiers, such as “The Fate of Gettysburg,” unless you have a warehouse to fit it in!

The next consideration is scale. For a small scene, such as “Desperation at Skull Camp Bridge,” we could use a larger scale because the scene would not involve a lot of figures. A scale of 2-inch-tall cats is okay if there are only sixty soldiers involved. But it would be impossible to use cats of that size for a to-scale diorama with 3,000 soldiers, such as “The Fate of Gettysburg,” unless you have a warehouse to fit it in!

On the evening of May 1, Lee met with Jackson. As they talked, Gen. Jeb Stuart rode up and told them the Union army’s right flank was in the air. Lee looked at Jackson. “What do you propose to do?”

On the evening of May 1, Lee met with Jackson. As they talked, Gen. Jeb Stuart rode up and told them the Union army’s right flank was in the air. Lee looked at Jackson. “What do you propose to do?”

The gray lines swarmed over the surprised Union soldiers, some of whom were so scared they couldn’t even fire their guns before being swept away by the gray juggernaut. The Union flank crumbled. By the time darkness halted the attack, two miles of the Union line had been rolled up.

The gray lines swarmed over the surprised Union soldiers, some of whom were so scared they couldn’t even fire their guns before being swept away by the gray juggernaut. The Union flank crumbled. By the time darkness halted the attack, two miles of the Union line had been rolled up. On the evening of April 9, 1865, Gen. Joshua Chamberlain received word that he would command the Union troops receiving the surrender of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Gen. Grant had been generous in his terms to Gen. Lee, but he did feel and insist that the Confederates should lay down their arms before Union troops representing the Union army. Chamberlain, feeling “this was to be a crowning incident of history,” asked his corps commander, Gen. Griffin, if he could use his old Third Brigade, who he had served with for two years and commanded after Gettysburg. “I thought these veterans deserved this recognition,” he recalled in his reminiscences. Griffin obliged, transferring Chamberlain to command of the Third instead of the First Brigade.

On the evening of April 9, 1865, Gen. Joshua Chamberlain received word that he would command the Union troops receiving the surrender of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Gen. Grant had been generous in his terms to Gen. Lee, but he did feel and insist that the Confederates should lay down their arms before Union troops representing the Union army. Chamberlain, feeling “this was to be a crowning incident of history,” asked his corps commander, Gen. Griffin, if he could use his old Third Brigade, who he had served with for two years and commanded after Gettysburg. “I thought these veterans deserved this recognition,” he recalled in his reminiscences. Griffin obliged, transferring Chamberlain to command of the Third instead of the First Brigade.

At the head of the first Confederate division, Gen. John B. Gordon rode, Chamberlain recalled, “with heavy spirit and downcast face.” Suddenly, a bugle rang out and the whole Union line “from right to left, regiment by regiment in succession,” shifted their rifles from “order arms” to “carry arms”—the soldier’s salute. Gordon “catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual,—honor answering honor.”

At the head of the first Confederate division, Gen. John B. Gordon rode, Chamberlain recalled, “with heavy spirit and downcast face.” Suddenly, a bugle rang out and the whole Union line “from right to left, regiment by regiment in succession,” shifted their rifles from “order arms” to “carry arms”—the soldier’s salute. Gordon “catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual,—honor answering honor.”