Today, we take a look at the personalities of some Civil War horses. Most of the horses below are unnamed, but the stories all show their individual characters. We might be surprised at how much goes on inside a horse’s head, if all we see is the animal dozing in the pasture. But as we read the stories of men and officers of the Civil War, we can see the sensitivity, courage, and personality of their horses. As with the men, the war brought out the mettle in the animals, showing the cowards and the heroes, the stoic and the sensitive.

Horses might seem to just plod through life, wherever we lead them, but in fact they are highly sensitive and observant animals. Henry Kyd Douglas, an aide to “Stonewall” Jackson, recalled his horse’s distress while passing through the Antietam battlefield during the night, after the fighting had ended.

Horses might seem to just plod through life, wherever we lead them, but in fact they are highly sensitive and observant animals. Henry Kyd Douglas, an aide to “Stonewall” Jackson, recalled his horse’s distress while passing through the Antietam battlefield during the night, after the fighting had ended.

The dead and dying lay as thick over it as harvest sheaves. The pitiable cries for water and appeals for help were much more horrible to listen to than the deadliest sounds of battle.… My horse trembled under me in terror, looking down at the ground, sniffing the scent of blood, stepping falteringly as a horse will over or by the side of human flesh; afraid to stand still, hesitating to go on, his animal instinct shuddering at this cruel human misery.

On the other end of the spectrum, horses could grow used to the chaos of war, giving them what seemed almost a philosophical outlook on life. Gen. John Gibbon noted such stoicism among the artillery horses of Cushing’s batteries while the bombardment raged and some 150 Confederate cannons focused on their location.

One thing which forcibly occurred to me was the perfect quiet with which the horses stood in their places. Even when a shell, striking in the midst of a team, would knock over one or two of them or hurl one struggling in his death agonies to the ground, the rest would make no effort to struggle or escape but would stand stoicly [sic] by as if saying to themselves, “It is fate, it is useless to try to avoid it.”

One thing which forcibly occurred to me was the perfect quiet with which the horses stood in their places. Even when a shell, striking in the midst of a team, would knock over one or two of them or hurl one struggling in his death agonies to the ground, the rest would make no effort to struggle or escape but would stand stoicly [sic] by as if saying to themselves, “It is fate, it is useless to try to avoid it.”

But sometimes, even cool-headed horses could lose it. When the bombardment began pounding Gen. Hancock’s II Corps before Pickett’s Charge, the general decided to ride along his corps’ line, to inspire the men and give them confidence. He was mounted on his usual black horse, a horse that had carried him in battle before. This time, the magnitude of the cannonade was too much for the animal and he began acting up. Unfazed, the general dismounted and switched to an aide’s tall, white-faced, light bay. With his coat flapping open to show his signature white shirt, Hancock calmly rode along his lines. Seeing their general’s example, a staff officer recalled, Hancock’s men “found courage longer to endure the pelting of the pitiless gale.” Hancock continued using the tall bay throughout the rest of his involvement in Pickett’s Charge.

Lt. Haskell on Dick

Lt. Frank Haskell, one of Gibbon’s aides, described his experiences during Pickett’s Charge in a letter to his brother after the battle. In it, he recalled the reaction—or lack thereof—of his horse, Dick, when the cannonade opened.

The General at the first had snatched his sword, and started on foot for the front. I called for my horse; nobody responded. I found him tied to a tree, near by, eating oats, with an air of the greatest composure, which under the circumstances, even then struck me as exceedingly ridiculous. He alone, of all beasts or men near was cool. I am not sure but that I learned a lesson then from a horse.

Dick remained steady throughout the following fighting. Despite a serious wound to his right thigh and three bullets in his body, Dick carried Haskell back and forth at the gallop as the lieutenant urged men forward and summoned reinforcements to repulse Pickett’s men. Not until their duty was over did Dick lie down and finally succumb to his mortal wounds. “Good conduct in men under such circumstances,” Haskell wrote, “…might result from a sense of duty—his was the result of his bravery.” Haskell finished by expressing his wish that, if there be a Heaven for horses, “in those shadowy clover fields [Dick] may nibble blossoms forever.”

Dick remained steady throughout the following fighting. Despite a serious wound to his right thigh and three bullets in his body, Dick carried Haskell back and forth at the gallop as the lieutenant urged men forward and summoned reinforcements to repulse Pickett’s men. Not until their duty was over did Dick lie down and finally succumb to his mortal wounds. “Good conduct in men under such circumstances,” Haskell wrote, “…might result from a sense of duty—his was the result of his bravery.” Haskell finished by expressing his wish that, if there be a Heaven for horses, “in those shadowy clover fields [Dick] may nibble blossoms forever.”

Today we take a look at our first to-scale diorama, “I Want You to Prove Yourselves,” which shows the 54th Massachusetts Infantry charging Battery Wagner in Charleston, SC, on July 18, 1863.

Today we take a look at our first to-scale diorama, “I Want You to Prove Yourselves,” which shows the 54th Massachusetts Infantry charging Battery Wagner in Charleston, SC, on July 18, 1863.

While some of the cats on the diorama represent identified historical officers and men, there is one cat whose importance is related to the history of Civil War Tails instead. At midnight on January 1, 2000, we installed Cat 3000. His number means that at the time he was made, we had 3,000 cats on our census. (Currently, we have 8,723.) To make him recognizable, we gave him a white feline (not human) “mustache” nose and a white tip on his tail.

While some of the cats on the diorama represent identified historical officers and men, there is one cat whose importance is related to the history of Civil War Tails instead. At midnight on January 1, 2000, we installed Cat 3000. His number means that at the time he was made, we had 3,000 cats on our census. (Currently, we have 8,723.) To make him recognizable, we gave him a white feline (not human) “mustache” nose and a white tip on his tail.

Now, Forrest rode to join Polk, but although he heard the firing, he could not catch up with the fight because Stanley’s cavalry pushed Wheeler’s men back so quickly. As the afternoon wore on, Wheeler decided Forrest was not coming and withdrew over Skull Camp Bridge. Just as the Confederates were about to burn the bridge, Maj. Rambaut of Forrest’s staff galloped up and said that Forrest was in sight of Shelbyville and would cross at the bridge.

Now, Forrest rode to join Polk, but although he heard the firing, he could not catch up with the fight because Stanley’s cavalry pushed Wheeler’s men back so quickly. As the afternoon wore on, Wheeler decided Forrest was not coming and withdrew over Skull Camp Bridge. Just as the Confederates were about to burn the bridge, Maj. Rambaut of Forrest’s staff galloped up and said that Forrest was in sight of Shelbyville and would cross at the bridge. Wheeler and his second-in-command Will T. Martin took 400 volunteers back across the bridge. They put up a short, hand-to-hand fight with sabers and carbines, and pistol butts as clubs, but the Union cavalry broke through Wheeler’s line and overran the two cannons he had brought with him. A caisson overturned on the bridge, blocking it. Union cavalry now stood between Wheeler’s men and the river.

Wheeler and his second-in-command Will T. Martin took 400 volunteers back across the bridge. They put up a short, hand-to-hand fight with sabers and carbines, and pistol butts as clubs, but the Union cavalry broke through Wheeler’s line and overran the two cannons he had brought with him. A caisson overturned on the bridge, blocking it. Union cavalry now stood between Wheeler’s men and the river.

One particularly interesting monument is that of the 5th New Hampshire on Ayres Avenue along the edge of the Wheatfield. It is quite memorable, formed by three large boulders supporting a massive slab on which another boulder sits. But even more striking is the choice of the veterans as they designed and located their monument. Commanding their brigade during the battle was Col. Edward Cross. While he was a fine officer who took good care of his men, his manner—including a highly critical personality and a strict sense of discipline—did not endear him to others, even prompting the officers of one regiment to view him as a tyrant. During the fighting near the Wheatfield on July 2, he fell mortally wounded. His last words were, “I think the boys will miss me. Say goodbye to all.” Mixed as feelings may have been of him on July 2, 1863, in 1886 the veterans of the 5th New Hampshire chose to honor him with their regimental monument. Not only is Col. Cross’ name included on the slab’s plaque, but the monument stands where he fell.

One particularly interesting monument is that of the 5th New Hampshire on Ayres Avenue along the edge of the Wheatfield. It is quite memorable, formed by three large boulders supporting a massive slab on which another boulder sits. But even more striking is the choice of the veterans as they designed and located their monument. Commanding their brigade during the battle was Col. Edward Cross. While he was a fine officer who took good care of his men, his manner—including a highly critical personality and a strict sense of discipline—did not endear him to others, even prompting the officers of one regiment to view him as a tyrant. During the fighting near the Wheatfield on July 2, he fell mortally wounded. His last words were, “I think the boys will miss me. Say goodbye to all.” Mixed as feelings may have been of him on July 2, 1863, in 1886 the veterans of the 5th New Hampshire chose to honor him with their regimental monument. Not only is Col. Cross’ name included on the slab’s plaque, but the monument stands where he fell.

The two Union batteries opened fire immediately. “Great gaps were torn in that mass of mounted men, but the rents were quickly closed. Then, they were ready.” As one, the massive column advanced. One Confederate recalled the anticipation: “It was the moment for which cavalry wait all their lives—the opportunity which seldom comes—that vanishes like shadows on glass. If the Federal cavalry were to be swept from their place on the right, the road to the rear of their center gained, now was the time.” The Confederates advanced in close columns of squadrons, first at a walk, moving “in superb style,” then at a trot. Finally, they leaped into a gallop, yelling “like demons.”

The two Union batteries opened fire immediately. “Great gaps were torn in that mass of mounted men, but the rents were quickly closed. Then, they were ready.” As one, the massive column advanced. One Confederate recalled the anticipation: “It was the moment for which cavalry wait all their lives—the opportunity which seldom comes—that vanishes like shadows on glass. If the Federal cavalry were to be swept from their place on the right, the road to the rear of their center gained, now was the time.” The Confederates advanced in close columns of squadrons, first at a walk, moving “in superb style,” then at a trot. Finally, they leaped into a gallop, yelling “like demons.”

The Union line along Little’s Run fired into the Confederate right, and bits and pieces of regiments charged—here a squadron, there a couple dozen men. Even Col. McIntosh charged with his staff and headquarters escort!

The Union line along Little’s Run fired into the Confederate right, and bits and pieces of regiments charged—here a squadron, there a couple dozen men. Even Col. McIntosh charged with his staff and headquarters escort!

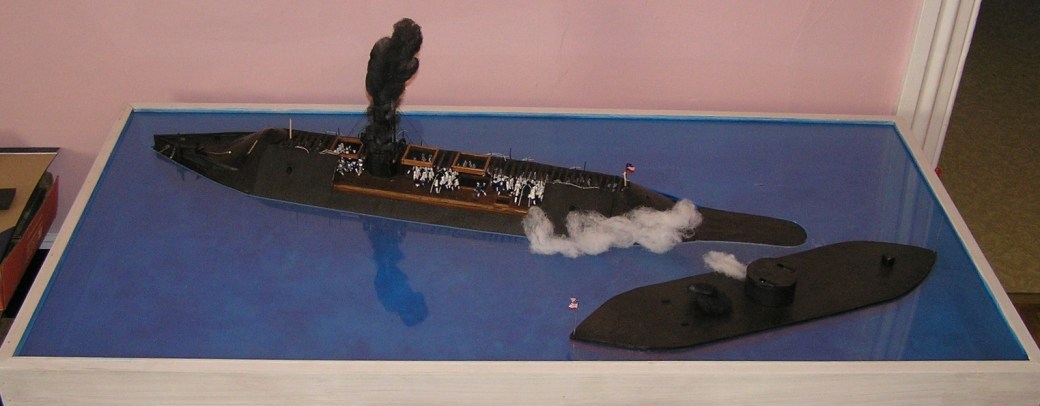

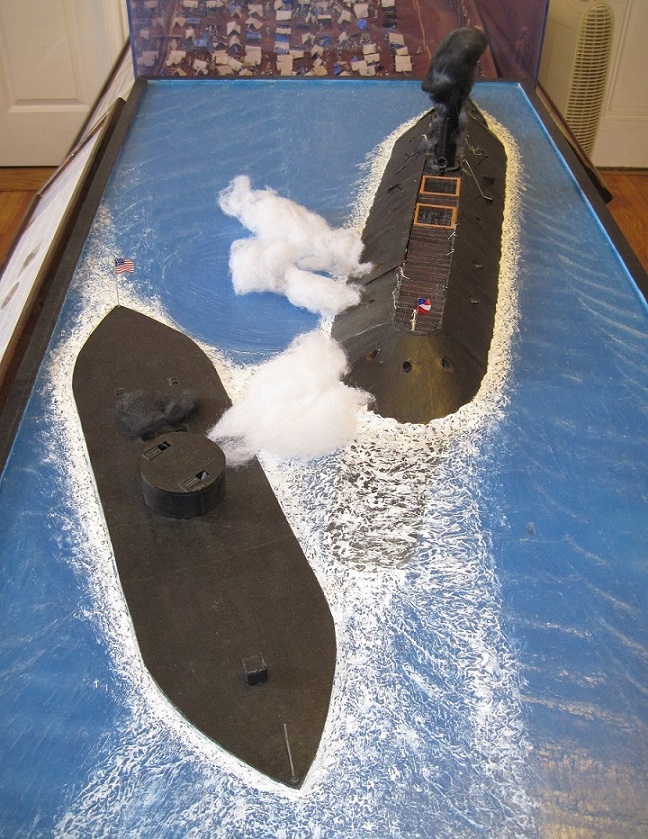

CSS Virginia in dry-dock. Ordinarily, we would have built the ships entirely of cardboard, but since Rebecca had just “inherited” some light wood from a fellow model-builder, she decided to experiment with making the hulls out of wood. Virginia’s bow and stern are made of wood that was shaped to the bulkheads, while the middle section is cardboard. The casemate (the “barn-roof” part) is all cardboard. Note the missing section of the casemate—this is so that part is removable to allow you to see inside. Removing the entire side is impractical since the curve of the ends of the casemate require them to be securely anchored to the side panels.

CSS Virginia in dry-dock. Ordinarily, we would have built the ships entirely of cardboard, but since Rebecca had just “inherited” some light wood from a fellow model-builder, she decided to experiment with making the hulls out of wood. Virginia’s bow and stern are made of wood that was shaped to the bulkheads, while the middle section is cardboard. The casemate (the “barn-roof” part) is all cardboard. Note the missing section of the casemate—this is so that part is removable to allow you to see inside. Removing the entire side is impractical since the curve of the ends of the casemate require them to be securely anchored to the side panels.

Here, a few of the future crew are inspecting the work on the upside-down hull. (You can also see that Civil War cats drive Ford Mustangs!)

Here, a few of the future crew are inspecting the work on the upside-down hull. (You can also see that Civil War cats drive Ford Mustangs!)

Monitor finished! Note the gap between her black upper deck and her red hull. This is for the plexiglass “water,” since the ship is made in two parts. The hull glues to the underside of the plexiglass, and then the deck rests on top and remains removable. In designing the ship, we had to make sure to remember to factor in the thickness of the plexiglass and the gap, so Monitor did not end up an extra 1/8 inch thick.

Monitor finished! Note the gap between her black upper deck and her red hull. This is for the plexiglass “water,” since the ship is made in two parts. The hull glues to the underside of the plexiglass, and then the deck rests on top and remains removable. In designing the ship, we had to make sure to remember to factor in the thickness of the plexiglass and the gap, so Monitor did not end up an extra 1/8 inch thick.